“The Phoenician Scheme” is a Political Inversion of Wes Anderson's Style

How his archetypes become a background for aesthetic revelation

Before we get started — it has been months since I’ve written a film review, in part because I’ve been far too busy to see many new releases, let alone to write about them. But with summer comes a lull, so I plan on catching up on some new releases and, in turn, publishing my reviews for them. I’ve missed writing here a great deal, and I cannot wait to continue!

It takes maybe thirty seconds of The Phoenician Scheme (all but three shots) before we see someone sliced in half. An unnamed jet passenger is torn to pieces by a bomb intended for Anatole “Zsa-Zsa” Korda (Benicio del Toro), a European mogul mostly in the business of cruelty, in a brief prologue that immediately sends Wes Anderson’s style into a tailspin.

The director isn’t a stranger to violence, but splattered blood and a severed torso is a swift departure from the abstracted slant his work usually takes. Physical violence in his films has often been stylized to the point of comic relief — a stabbing with lefty scissors that inexplicably results in a motorcycle in a tree (Moonrise Kingdom) or a citywide revolution spurred just to gain access to girls’ dormitories (The French Dispatch). Awkward, stilted physical comedy often offers a bit of levity for the raw emotional brutality at the core of his films.

Anderson uses this initial violent encounter as a tonal primer for the body of The Phoenician Scheme, the latest installment in recent existential pastiche that is less interested in its own story than it is in understanding the creation of it. Like Asteroid City before it, the film is a cross-section of Anderson’s own aesthetic, but at the opposite end of a philosophical spectrum.

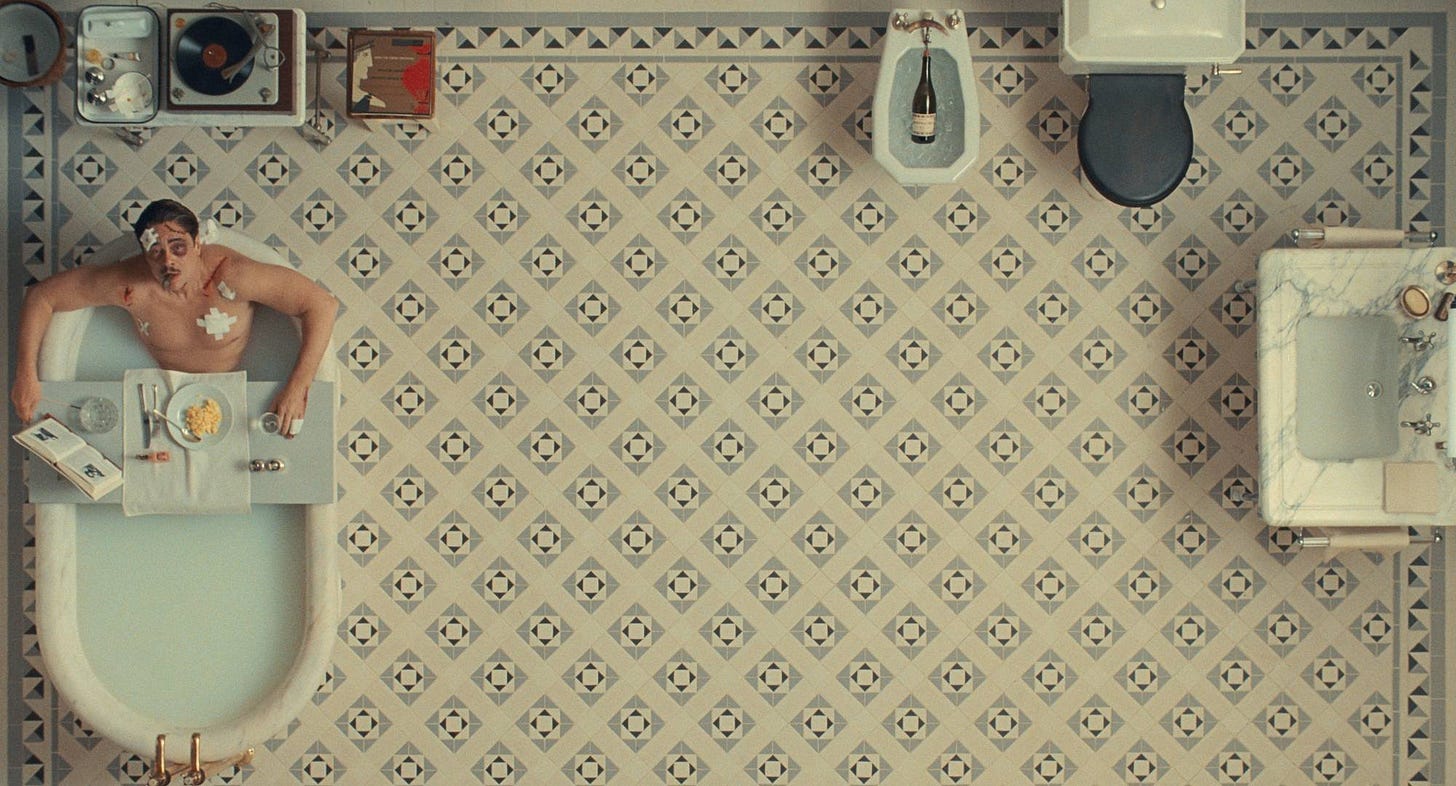

While Asteroid City elevated artifice to the point of total collapse, The Phoenician Scheme simplifies it into intentionally rigid archetypes. The film follows Zsa-zsa after he appoints his eldest and only daughter, a devout nun (Mia Threapleton), as the heir to his fortune. Together they make pit stops on their journey through a Middle East dollhouse travelogue in search of financing for his largest international enterprise.

The story operates at a greater scale than Anderson has attempted before, but feels intentionally and narratively stagnant. Each episodic encounter is carefully introduced, enacted, and resolved, and stylistic layering simply acts as aesthetic dressing for a cut-and-dry narrative. Each character is a paradigm of Anderson’s usual archetypes: a broken father seeking to repair an estranged relationship, a deadpan young woman with strong moral conviction, and an awkward young male love interest with niche expertise wearing mid-century menswear, all forming an uncomfortable but endearing familial love triangle.

But while the characters fit the bill of the usual Anderson lineup, they feel almost intentionally neglected, overpopulated with quirks that can’t quite compensate for their total emotional flatness. It’s initially off-putting, and the first episode of the caper is so stilted that I began to wonder if the lazy “Anderson is a parody of himself” critics were right all along.

But slowly, The Phoenician Scheme begins to take form and the paradox of the film’s dense emptiness starts to crystallize. It is a complete cross-section of his style, elevating the usual dollhouse charm of his technique while dissecting all his tendencies down to their basic form. It’s not just overtly physically violent, but artistically cruel, dangling our favorite Anderson-isms in front of our faces but skeletonizing them in the process.

It’s no coincidence, then, that The Phoenician Scheme is one of Anderson’s most spiritual films. Zsa-zsa, who spends the whole film routinely escaping death, interrupts the absurd arbitrations of financial dealing with religious framing — a purgatorial trial for the future of his soul. The biblical tableaus are populated with a cast of Anderson regulars as prophets and other heavenly figures (including Bill Murray as God), but they hold an aesthetic melancholy that creates friction against the otherwise playful images.

Zsa-zsa has invoked widespread suffering, which, in his eyes, is all justifiable collateral for his enterprise. But for the first time, the stronghold of Anderson’s villain is real and deeply cruel, not a pantomime of an assumed evil (like the fascists in The Grand Budapest Hotel) but a mogul of famine and slavery.

This time, authoritarianism isn’t a moral backdrop for an escapist, endearing tale. Instead, Anderson’s usual archetypes are the backdrop for a political crisis of faith, for a soul on trial. The pastel colors and monotone-lighting-speed-ultra-hyphenated dialogue can’t keep the world out anymore. Whimsy is the chaser for, not the distraction from, a global market of cruel deal-making. It is a slow revelation that escapism might still be a manifesto for the worst ravages of capitalism.

If Asteroid City was an assurance of his emotions, and The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar was a fable for his constructions, The Phoenician Scheme is Anderson’s admission of guilt to accusations of emptiness and artifice. But this admission gives work a depth like never before. Despite a recognition of the mortality of his style, Anderson insists that cruelty itself is mortal as well.

OVERALL SCORE: 9/10

The Phoenician Scheme was released on June 6, 2025, and is currently showing in U.S. theaters.

. . . it's good, would you like a bite?