The Delirious Dissonance of “Beau is Afraid”

Ari Aster’s highly-anticipated epic is a surreal voyage into the recesses of guilt and gratitude

Ari Aster has quickly and spectacularly established himself as one of the most influential modern film directors, with Midsommar and Hereditary pioneering a mainstream rebirth of psychological horror. His third film, Beau is Afraid, takes a sharp left turn, breaking out of his usually tighter horror mold. While still rooted and connected to the haunting core themes of his earlier work, Aster approaches his latest film from a jocular and charming perspective. A hero’s journey undertaken by possibly the least apropos protagonist ever conceived, Beau is Afraid avoids a typical horror structure and instead becomes a nightmare-ish three hour Odyssey.

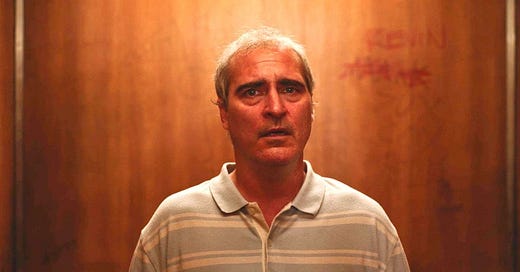

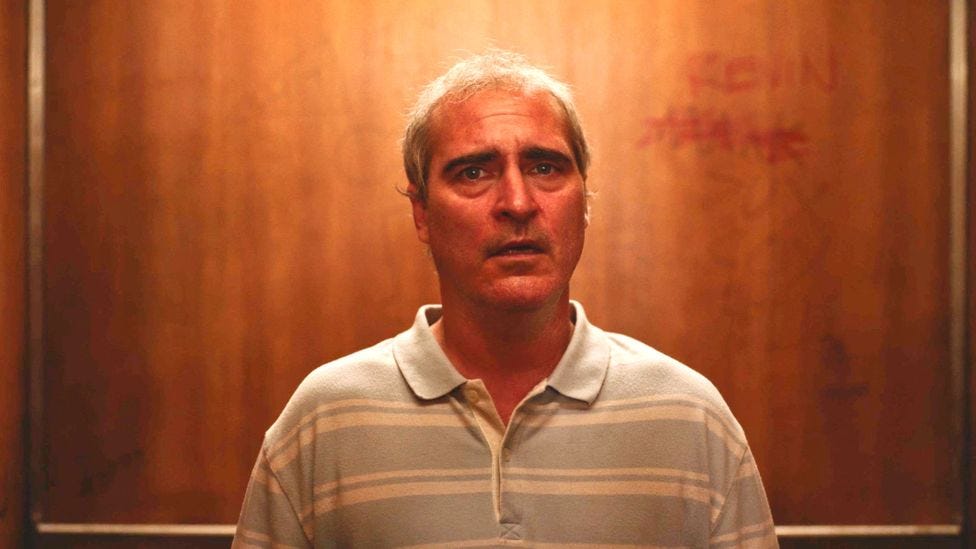

Beau is Afraid’s eponymous main character (Joaquin Phoenix) is an aging and unmarried man subsumed by anxiety, who resides in a lawless version of New York. A queasy stereotype of an ennui-riddled, anxious, Jewish man, Beau wallows in the utter lack of control he seems to have, a sinister version of A Serious Man’s Larry Gopnik. Incited by a single word that his therapist scribbles down during the first scene of the film, Beau’s journey is fraught with an overwhelming and crippling sense of guilt. This guilt is weaponized by nearly everyone around him, intentionally or unintentionally, generating a delirious and eclectic voyage in which Beau’s worst anxieties constantly come to fruition and he must bear the consequences of actions of which he claims no responsibility.

Illustrated through Aster’s now-iconic visual tableau, the first act of the film is a chaotic and frenzied chronicle of Beau’s life as he prepares to visit his overbearing mother. In Beau’s America-gone-mad, suicide generates public entertainment, AR-15s are pedaled on the streets, and Beau faces unwarranted and violent harassment from neighbors and locals despite his desperate inconspicuousness. As Beau journeys deeper into his own ego, he finds himself encountering a slew of parodized American archetypes, including a WASPy family bereft by the loss of their soldier son, who use their pristine affluence to try to mask the chaos embedded within their own crumbling nuclear household. Aster’s dark comic image of America is one riddled with anxiety, whether in the lawless city scattered with bodies or in an uncomfortably quiet suburbia.

As the film progresses and slowly enters a more cerebral realm, Beau’s episodic interactions become increasingly confusing and jarring. After being led by an off-the-grid theater troupe through a metacontextual interlude akin to a children’s tale, Beau is Afraid becomes increasingly self-reflective in its structure. What becomes evident during Beau’s journey is not that he is navigating his anxiety, but rather he is being piloted by it. As Beau continues his feverish adventure, Aster balances realism and fantasy to create a seriocomical metaphor for a lifetime of emotional manipulation and exploitation. Beau’s internal battle finally stretches him to such an extreme point of tension that there can be no solution except for his reality to snap and collapse in on itself.

Through an upsetting kaleidoscope of painful situations, Aster uses the friction of physical discomfort to propel a largely plotless and labyrinthine narrative of personal suffering and abreaction. Beau is Afraid somehow meshes emotional catharsis and crippling unease into a laborious watch that is sometimes incisive and sometimes facile: an overwhelming and exhausting spectacle.

OVERALL SCORE: 8/10

Beau is Afraid was released on April 21, 2023 and is currently in US theaters.

The Red Owl in Bloomington . . .