There is no secret to unlock in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. No extreme underlying allegory, no hidden subplot which unearths an elusive history. The film is about abuse: how it manifests itself, and how debilitating it can be. Many have theorized, most notably in 2012’s documentary Room 237, that an intentional hidden allegory is present under the horror story of a father plotting to murder his family when they are isolated by snowstorms in a remote mountain hotel. But upon continual rewatch, the conventional horror effects wear off and the reality of Jack’s abuse becomes increasingly chilling. The hotel did not turn Jack into a monster; its isolation created the ideal environment for him to lash out and for his family’s darkest fears to become reality. Jack was not possessed by the hotel’s traumatic history — he has always been haunted and Jack’s relationship with his family has always been abusive. He has always been the caretaker.

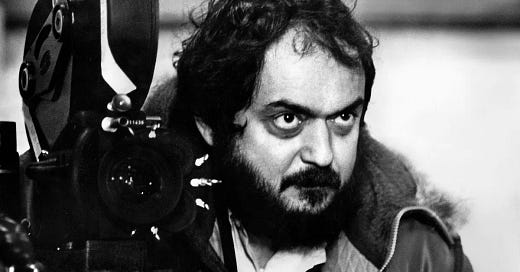

Despite the film’s acute dissection of reconciliation with abuse, the notorious control and terror exercised by Kubrick during The Shining’s production are as infamous as the film’s most iconic moments are famous. To the detriment of his actors, primarily Shelley Duvall, Kubrick fully embraced the mythos of the omnipotent auteur, operating under the notion that maintaining absolute authority over his collaborators was the singular method to secure his creative vision. Because of Kubrick’s domination, Shelley Duvall endured intense emotional manipulation and psychological abuse, and Kubrick created a production environment virtually indistinguishable from the narrative he crafted.

Since the release of the film, and Kubrick’s death nearly two decades later, Duvall and other actors, specifically Malcolm MacDowell, have opened up about Kubrick’s abusive behavior. Subsequently, audiences have become fascinated with the dark sides of revered creatives, rightfully demanding that abuse of power faces accountability no matter the impact of the art born out of it. Simultaneously, in an increasingly cynical critical landscape, many viewers are intrigued and even excited to condemn beloved artists who are not as deserving of the worship bestowed upon them by the general public.

But while Duvall mourns the abuse she faced on set, she is proud of her product. She believes her revolutionary performance would not have been possible without Kubrick’s on-set behavior, and she hopes viewers will recognize her resilience and artistry rather than limiting the perception of her participation in the film to that of a victim of unchecked control. While a newfound distaste for the film is born out of empathy for those silenced by power, actively supporting Duvall must entail celebrating her talent and humanity in the face of misogyny and abuse. She was more than a pawn in Kubrick’s world: she is a survivor and an incredibly talented performer, and her agency as an artist is stripped from her when her legacy in the film is reduced to that of a victim. Discounting The Shining entirely due to Kubrick’s behavior falls in line with the biggest myth of auteurism — the one that put him in the position to be abusive in the first place — that the film is exclusively a product of a sole visionary with complete creative control, and therefore the work of the other collaborating artists is irrelevant to the legacy or value of the film.

Kubrick is not the only director whose desire for complete creative control of their filmography led to abuse or exploitation of their collaborators. Francois Truffaut’s theory of auteurism, originally explained in his 1954 essay “A Certain Tendency of French Cinema,” posits that directors are akin to literary authors, and established a standard of lauding directors as gods that ruled over their sets. Film movements in Europe, such as the French New Wave, created a new cultural understanding that directors were metteurs en scene, visual mediators of narratives who worked their own personalities into the stories they transcribed for the stage or screen. Truffaut established the theory that the director was the true artist behind a film, and other collaborators, such as screenwriters, were apprentices in their vision. In fact, devaluing of writers in the face of studio and directorial sovereignty over productions continues to drastically impact the writers’ compensation.

From the 1930s until the late 1950s, Hollywood was governed by a series of strict studio regulations, most famously the Hays Code, that prevented the slightest provocation or subversion in art. Audiences began to crave thoughtful, artistically minded films that provided an insight into humanity which studio commissions couldn’t capture. As new independent films began to dominate the American box office in the 1960s and 70s, the ideology of the auteur began to grasp film productions. While auteur theory served to undermine the dominance of the studio system, it also continued to help maintain a standard of anti-collaborative thought in an inherently collaborative medium, and an environment of abuse formed in the shadow of a homogenous directorial class.

Auteurism brought about some of the most iconic and important art and artists of the 20th century, but it discredits the painstaking and revolutionary creativity of many whose contributions are deemed unworthy of marquee status. A Nightmare Before Christmas is a perfect example. Marketed as “Tim Burton’s” masterpiece because of his already established status as an auteur, it was in fact directed and animated by Henry Selick and his artistic team. Because advertising the film as a part of Burton’s stylistized artistic canon dramatically increased profitability, Selick’s and others’ involvement was minimized and virtually forgotten by generations of viewers.

Auteurism developed in an effort to elevate creative visionaries and subvert purely profit-minded studios, but it became a standard that justified abusive or controlling behavior as a part of the filmmaking process. However, the revolution of the controlling and omniscient auteur, intentionally or not, brought about a wave of insightful and sensitive films about abuse and control. Besides The Shining, the best example of this is Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo. The film follows an eccentric entrepreneur who dreams of building an opera house in the Peruvian Amazon. In order to finance his project, he sets out via boat to collect and sell rubber in the colonially uncontacted regions of the Amazon Rainforest. Increasingly obsessed with his project, Fitzcarraldo (Klaus Kinski) exploits the labor of countless natives to hoist his boat up and over a mountain rather than traverse a section of dangerous rapids. Fitzcarraldo is an examination of the unchecked obsession of a cruel capitalist, and a violent condemnation of imperialism and exploitation — painted on the canvas of the film’s own brutal production history. Herzog set off into the Amazon with a small film crew and severely limited resources, cast the crazed and abusive Klaus Kinski as his star, and deforested an entire hillside while exploiting the labor of the Machiguenga tribe as extras to create the colonial spectacle of a boat summiting a mountain.

Both Herzog and his protagonist, on a quest for their art, discount the labor of their collaborators to bask in the awe of the man-made, spilling blood as they continue along their path. And for both Herzog and Fitzcarraldo, nature gets its revenge. It plays tricks on the senses of Fitzcarraldo, and seeks justice for the bloodshed. During the film’s production, the chief of the Machiguenga tribe offered to kill Kinski, whose blatant disrespect on set worsened an already tenuous relationship with Herzog. The invasive nature of the production resulted in several serious injuries for the crew, whose irresponsibility at the demands of Herzog led to a snakebite resulting in an amputation, a paralyzing plane crash, and deaths of indigenous extras. Both inside and outside of the film, unchecked power resulted in colonial demolition and subsequently, disaster in the face of this hubris. The set of Fitzcarraldo was even burnt to the ground three years before the release of the film by the Aguruna tribe, seeking retribution against Herzog who attempted to build a whole village on their land without the consent of local leaders.

Fitzcarraldo proves that auteurism, fed by the promise of complete control, leads to disaster on both individual and global levels, but also gives us thoughtful insight into how definitive artistic hierarchy manifests itself, and how it unwinds into horror. The myth of the auteur leads to both great pain and great art, and is so entrenched in our understanding of classic cinema that untangling it appears to be a lost cause. But there is hope.

For the past six years or so, Hollywood has entered a phase of increased accountability, as powerful and abusive men face scrutiny, boycotts, and occasionally incarceration for their crimes. Society can now provide increased scrutiny from those affected by abuse, who can now amplify their voices in the court of public media. Simultaneously, a culture of increased accountability has led to a focus on punishment and condemnation rather than change. The fleeting catharsis of retributive glory results in an over-emphasis of the utility of our justice and punishment system, and undermines reform needed to help the lives of the less powerful and the many wrongfully incarcerated. While the importance of being held accountable cannot be understated, we need to strive for a culture in which punishment is not glory, and real change starts from rethinking the theories and structures that build exploitative industries. Reframing this conversation through art can catalyze a shift in the cultural understanding of artistic hierarchy, and the release and success of TÁR last year indicates an interest in this shift.

As I wrote in my individual review of the film, TÁR uses a contemporary lens to capture the cruel milieu of the auteur in a timeless manner. The film emphasizes this thesis in its first few seconds, where the entire team of collaborators is credited at the beginning of the film, with credit for director Todd Field and star Cate Blanchett appearing last. These credits allow the viewer to face the pain, the creativity, the splendor, and the labor that goes into the art that we all enjoy. TÁR follows accomplished composer and conductor Lydia Tár approaching a career milestone, until the reality of her manipulative and controlling behavior becomes public. For Lydia, an environment of abuse is sometimes a necessary step for her to maintain control over her art (even in an inherently collaborative medium such as an orchestra). As a conductor, Lydia controls time itself, and the external natural rhythms of her environment serve as an aggravating loss of her control and a glimpse into the festering guilt of her behavior.

TÁR demonstrates that artists can be blinded and preoccupied by control, which corrupts their pieces’ relationships with both the creators and its audience. Lydia is corrupted by her environment, and she attempts to implicate the audience by convincing us to be on her side. But TÁR’s intentional ambiguity of objective reality never studies whether her punishment is merited or not. Instead, it dissects the structure of lucrative art industries that allow artists to pursue control rather than creativity. Art is a conversation, not a lecture, and in the final shot of the film, TÁR shows us the other party in the conversation for the first and only time. Lydia is stripped of her position conducting an elite orchestra and moves to the Philippines to conduct video game soundtracks, and, for possibly the first time in her career, her art is not about her ego nor her control. When the film cuts to the audience, we come to the reality that no one is there to gawk at the auteur that is Lydia Tár, they are there to experience art. The moment is not about her, and it never should have been about her. It has always been about us.

So, moving forward, how do we rethink film as the work of a collective body rather than a sole creative visionary? First, rethinking auteurism does not absolve abusive auteurs from responsibility for their actions. Many of those who fall victim to this abuse are also featured in the auteur’s work; we must create a dialectic that balances a skilled artist’s work with their horrifying behavior, while celebrating the art of their survivors, communally created in the face of pain and abuse. Second, art is never a definitive process, and even those who develop the most influential methods often rethink their theory upon seeing a negative impact. Stanislavsky, the so-called father of method acting, revised his own theory when he saw the toll it was taking on actors who implemented it, diverging from the fully-developed Stausbaurg version, and developing a theory of imagination to evoke character. And while we still get the Jared Letos and Dustin Hoffmanns of the acting world, our environment is evolving toward one that condemns the ideas behind method acting and its outcomes.

Ultimately, for-profit industries are fundamentally hierarchical, and the products they pump out will be infected by this cultural disease, however collaborative they may be. Yes, directors play a significant role in shaping and bringing stories to life on screen, but their involvement in bringing a film to fruition is not justification for abuse, and I think the antidote for the abusive system is to shift the cultural perspective to one that understands film as a wholly collaborative endeavor. Whether that means looking back and rethinking Kubrick and Duvall’s dynamic on the set of The Shining, or moving forward, like Martin Scorsese reworking his entire screenplay for Killers of the Flower Moon after collaborating and receiving input from the Osage nation, rethinking our perception of collaboration is a tangible objective. Progress begins by reframing the story.

Thank you, this is the most thoughtful piece I've read on film. I don't read about film. But I'd like to start reading your work.

That is a fantastic bag, by the way.