“Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse” Is an Honest Journey Through Breathtaking Psychedelia

Superhero movies don’t need to find the lowest common denominator of filmmaking

For nearly thirty years, animation has been dominated by a style that Vox video producer Edward Vega identifies as “photo-surrealism” — entirely digitally-rendered, featuring stylized characters in hyper-realistic environments complete with digitally created focal lengths and bokeh. Pixar pioneered and refined this sleek digital look with lucrative results, spurring a trend of homogenous animation styles from studios like DreamWorks and Sony. Consequently, studios stopped experimenting with pushing the boundaries of animation by locking down this hackneyed visual style that guaranteed profit. Soon, the “Pixar style” became the industry standard, and popular animation was shoehorned into a single style.

The rise of the Marvel Cinematic Universe similarly put restraints on the creative expansion of comic book films. Marvel’s success established a formulaic standard for superhero movies which take the fewest risks to maximize appeal. Both the standardization of animation and comic book movies created a pattern of making products that are not ideologically nor stylistically challenging. The calculation has been that when popular art does not challenge beliefs or artistic familiarity, it will reap maximum profit.

2018’s Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse broke the restrictive conventions of both modern animation and comic book filmmaking. The film came at what might be considered the culmination of the superhero movie trend, as the death of Stan Lee and the apparent end to the Avengers franchise appeared to bring closure to the cultural phenomenon. But as always, popular genres reinvent themselves because audiences continue to crave art that they see themselves reflected in. Into the Spider-Verse was a hyper-stylized, hyper-self aware reinvention of one Marvel’s most often reinvented characters; in this case a deconstruction of the idea that “anyone can be a superhero” creating a chaotic frenzy that overrides the idea of a monolithic savior.

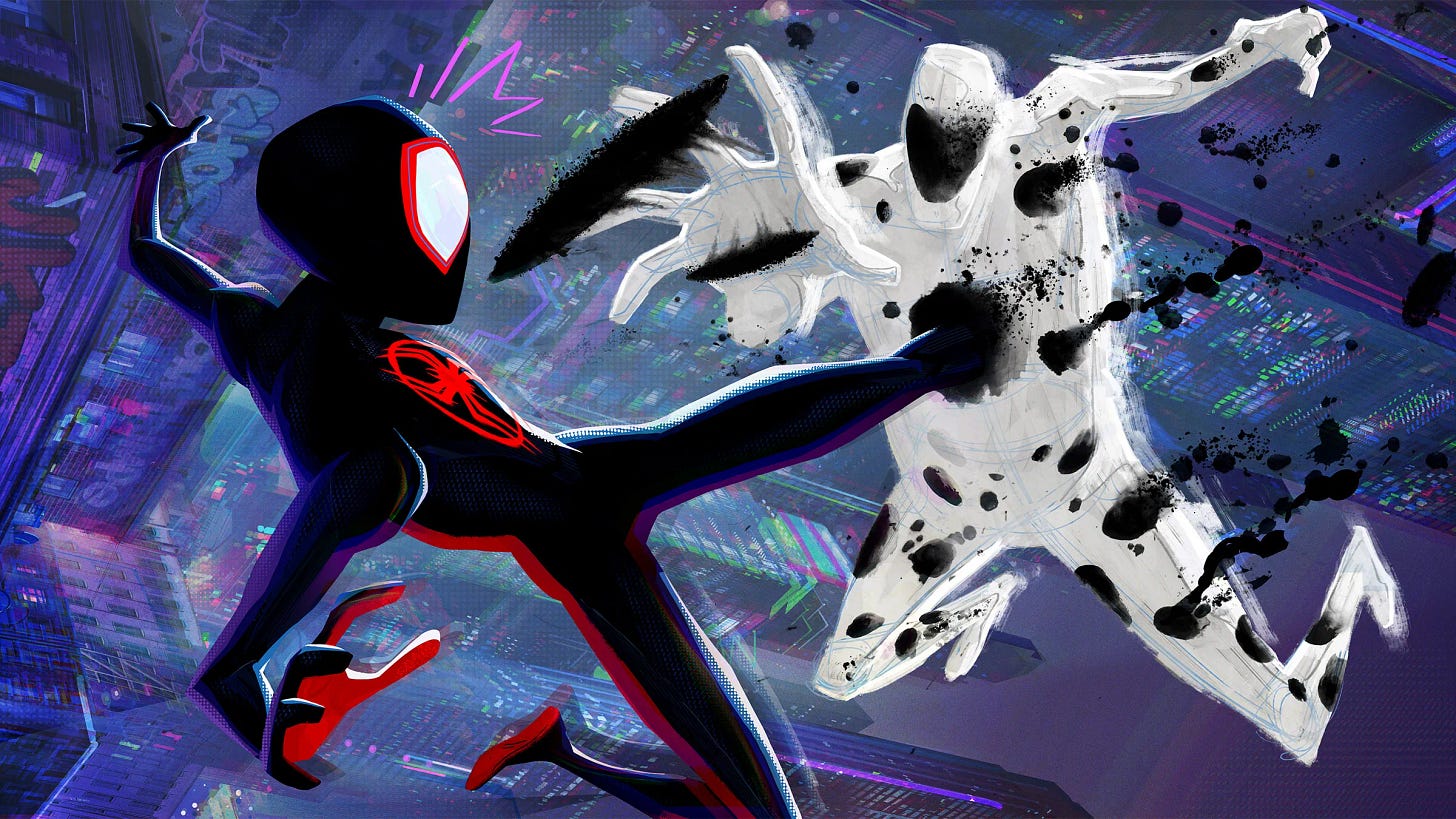

When Into the Spider-Verse’s contemporary sequel, Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, hit theaters last week, viewers were subjected to a dynamic and overwhelming narrative so undeniably thrilling that its conventional subplots do not undermine its success. Across the Spider-Verse takes its predecessor’s style of watching a comic book come to life and multiplies it by ten, creating a gorgeously dissonant story that rejects the visual tenets of modern animation and modern comic book movies.

The film reunites its protagonist, Miles Morales (Shameik Moore) with his home streets of Brooklyn, as he balances keeping order with maintaining his personal life. But amid family struggles and the introduction of a new antagonist, Miles reconvenes with his former accomplice Gwen Stacey (Hailee Steinfeld) and renters the multiverse. He encounters the Spider Society, a collection of Spider-People from infinite universes all determined to uphold the rules of the multiverse, an encounter that throws Miles into an internal battle between convention and finding his own path.

Across the Spider-Verse examines Miles’ discontent with living life by the standards of others, using the lens of diverging from a narrative canon to structure this transgressiveness. The storyline is executed flawlessly and uses metatext with a level of confidence that most superhero movies do not trust their audiences to understand. The film considers if personal identity and family loyalty always have to be at odds, and uses the structure of a multiverse to examine this theme rather than using excessive stimulation simply for its own sake. Across the Spider-Verse works so well because it accepts its audience as more than consumers, and entrusts us with the patience, creativity, and ability to comprehend complexity that we deserve.

Across the Spider-Verse uses the fundamental “anyone can be a superhero” conceit of comic book stories to examine the melancholy responsibility that comes with the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Maturity is both liberating and exhausting, and while Miles seeks personal freedom, he also carries the weight of familial expectations. While most superhero movies build upon the same conservative abstraction of an oversimplified good-bad spectrum — rugged vigilantes or unregulated individualists police cities to maintain law and order against agents of chaos — Across the Spider-Verse uses the idea of “great power and great responsibility” as its maturing protagonist learns the differences between individualism and individuality, between guidance and authority, between collectivism and control.

Unlike some of its Marvel contemporaries, dripping with conservative preachiness usually reserved for televangelist programs, Across the Spider-Verse does occasionally and frustratingly align itself with regressive ideas. The film's emotional beats land with uncomfortable and out-of-place copaganda, as Miles reconciles with his police officer father. Additionally, its visual and narrative psychedelia contrast its flat dialogue and sporadic emotional involvement. The film is overstuffed with cameos, references, and fan service (material of no direct relevance to the story included simply to appease fans of the franchise), so raw and well-developed moments sometimes feel deprioritized for a rapid-fire round of recognizable Marvel properties. This dexterity in balancing a well-told story with a 140 minute marketing campaign forces the film to peter out before its ending, leaving an exhausted, albeit very compelling, cliffhanger.

The film’s imaginative combination of breathtaking artistic styles and widely resonant themes compensate for its frustrating fan service and occasional conventionality. Across the Spider-Verse is a rare instance in which the second film in a trilogy does not feel like a bridge between the first and last installments. Instead, the plot combines narrative complexity with the thrill of pure spectacle. It’s not perfect, but for a Marvel property, it might be the best we ever get.

OVERALL SCORE: 8/10

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse was released on June 2 and is currently in US theaters.

Okay, you’ve convinced me to see this, even though like Luiza I’m not much of a Marvel fan. Although I do enjoy animation.

Perhaps the narrative analog to the “photo-surrealism” of the animation would be the pseudo-realism of Marvel’s stories. I always found Stan Lee to be kind of a one-note writer. Always the New York setting, always too much unnecessary dialogue, always the shady milieus from pulp magazines and bad film noir. But where Chandler’s Philip Marlowe mocked his underworld opponents, how their speech and gestures were copied from what they saw on screen, years later we were still getting these same characters and settings from Lee as though they reflected some kind of urban reality.

Lee’s best stuff was when he had someone like Jack Kirby, an artist with an actual visual imagination, to bring it to life.

It’s always worth contrasting the artistic vision of Lee and Kirby, New York-born sons of immigrants, with that of their exact contemporaries, those other immigrant sons, Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, who created Superman. But Shuster and Siegel hailed from Cleveland, not New York. Perhaps sensing they did not live in the center of the universe, their world always felt more unrealistic, more deliberately fictional, so that Superman lives in Metropolis, for example, not New York.

I can’t help but think that some of the differences in these visions still hold in comic book movies. Obviously, Lee’s vision won out, just as the fiction of Hemingway and Steinbeck won out over that of, say, Kafka. Of course, today’s comic book movies are created by committees, but perhaps to coin a proverb, once the channel has been dug, it’s hard to change the water’s course.

Here’s an example of Lee and Kirby at their worst (the speech bubbles almost crowding out the art) and their best (that image of the Blob refusing to be moved):

https://earthsmightiestblog.com/the-x-men-3-1964-1st-blob/

Reading so much good things about this movie! Although I’m not a Marvel fan, I’ll check it out. It seems pretty worth it.